Ap Art History Lost Wax Technique Lost Wax Technique

Liquid bronze at 1200 °C is poured into the dried and empty casting mould

A model of an apple in wax

From the model a rubber mould is made. (The mould is shown here with a solid bandage in plaster)

From this rubber mould a hollow wax or paraffin cast is made

The hollow paraffin apple is covered with a last, fire-proof mould, in this case clay-based, an open view. The cadre is also filled with burn-proof material. Note the stainless steel core supports. In the next footstep (not shown), the mould is heated in an oven upside-down and the wax is "lost"

A bronze bandage, still with spruing

On the left is an case of a safety mould, often used in the lost-wax process, and on the correct is the finished bronze sculpture.

Lost-wax casting (as well called "investment casting", "precision casting", or cire perdue which has been adopted into English from the French, pronounced [siʁ pɛʁdy])[i] is the process by which a indistinguishable metallic sculpture (oftentimes silverish, gold, brass or bronze) is bandage from an original sculpture. Intricate works can be achieved past this method.

The oldest known instance of this technique is a six,000-year old amulet from the Indus Valley Culture.[2] Other examples from somewhat after periods are from Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium B.C.[iii] and the objects discovered in the Cave of the Treasure (Nahal Mishmar) hoard in southern Palestine (region), which belong to the Chalcolithic period (4500–3500 BC). Conservative estimates of historic period from carbon-14 dating engagement the items to c. 3700 BC, making them more than than 5,700 years erstwhile.[4] [5] Lost-wax casting was widespread in Europe until the 18th century, when a slice-moulding process came to predominate.

The steps used in casting pocket-sized statuary sculptures are fairly standardized, though the process today varies from foundry to foundry. (In modern industrial utilize, the process is called investment casting.) Variations of the process include: "lost mould", which recognizes that materials other than wax tin can exist used (such as tallow, resin, tar, and textile);[6] and "waste material wax process" (or "waste mould casting"), considering the mould is destroyed to remove the cast detail.[seven] [eight]

Procedure [edit]

Casts tin be made of the wax model itself, the directly method, or of a wax re-create of a model that need not be of wax, the indirect method. These are the steps for the indirect process (the direct method starts at footstep 7):

- Model-making. An artist or mould-maker creates an original model from wax, clay, or some other material. Wax and oil-based clay are ofttimes preferred because these materials retain their softness.

- Mouldmaking. A mould is made of the original model or sculpture. The rigid outer moulds contain the softer inner mould, which is the exact negative of the original model. Inner moulds are normally made of latex, polyurethane rubber or silicone, which is supported by the outer mould. The outer mould can be made from plaster, but can likewise be fabricated of fiberglass or other materials. Nearly moulds are made of at to the lowest degree 2 pieces, and a shim with keys is placed between the parts during construction so that the mould tin can exist put back together accurately. If there are long, thin pieces extending out of the model, they are often cut off of the original and moulded separately. Sometimes many moulds are needed to recreate the original model, particularly for large models.

- Wax. Once the mould is finished, molten wax is poured into it and swished around until an even coating, unremarkably nearly 3 mm ( one⁄8 inch) thick, covers the inner surface of the mould. This is repeated until the desired thickness is reached. Some other method is to fill up the entire mould with molten wax and let it absurd until a desired thickness has assail the surface of the mould. After this the residuum of the wax is poured out again, the mould is turned upside down and the wax layer is left to cool and harden. With this method information technology is more hard to control the overall thickness of the wax layer.

- Removal of wax. This hollow wax copy of the original model is removed from the mould. The model-maker may reuse the mould to make multiple copies, limited only by the immovability of the mould.

- Chasing. Each hollow wax re-create is then "chased": a heated metal tool is used to rub out the marks that show the parting line or flashing where the pieces of the mould came together. The wax is dressed to hide whatsoever imperfections. The wax now looks like the finished piece. Wax pieces that were moulded separately can now exist heated and attached; foundries oftentimes use registration marks to indicate exactly where they go.

- Spruing. The wax re-create is sprued with a treelike structure of wax that volition eventually provide paths for the molten casting material to flow and for air to escape. The carefully planned spruing usually begins at the superlative with a wax "cup," which is fastened by wax cylinders to various points on the wax copy. The spruing does not have to be hollow, as it volition exist melted out later in the process.

- Slurry. A sprued wax re-create is dipped into a slurry of silica, and so into a sand-like stucco, or dry crystalline silica of a controlled grain size. The slurry and dust combination is called ceramic beat out mould textile, although it is non literally made of ceramic. This vanquish is allowed to dry, and the process is repeated until at least a one-half-inch coating covers the entire slice. The bigger the slice, the thicker the beat needs to exist. Only the inside of the cup is not coated, and the loving cup's flat top serves as the base of operations upon which the slice stands during this process. The core is also filled with fire-proof material.

- Burnout. The ceramic shell-coated slice is placed cup-downwards in a kiln, whose rut hardens the silica coatings into a beat, and the wax melts and runs out. The melted wax can exist recovered and reused, although it is often but burned up. Now all that remains of the original artwork is the negative space formerly occupied by the wax, inside the hardened ceramic beat out. The feeder, vent tubes and cup are also now hollow.

- Testing. The ceramic shell is immune to absurd, then is tested to meet if water will flow freely through the feeder and vent tubes. Cracks or leaks can be patched with thick refractory paste. To examination the thickness, holes can be drilled into the crush, so patched.

- Pouring. The shell is reheated in the kiln to harden the patches and remove all traces of moisture, then placed loving cup-upwards into a tub filled with sand. Metal is melted in a crucible in a furnace, so poured carefully into the trounce. The beat out has to exist hot because otherwise the temperature divergence would shatter information technology. The filled shells are then allowed to cool.

- Release. The shell is hammered or sand-blasted abroad, releasing the rough casting. The sprues, which are also faithfully recreated in metal, are cut off, the material to be reused in some other casting.

- Metal-chasing. Just every bit the wax copies were chased, the casting is worked until the telltale signs of the casting process are removed, and so that the casting at present looks like the original model. Pits left by air bubbles in the casting and the stubs of the spruing are filed down and polished.

Prior to silica-based casting moulds, these moulds were made of a variety of other fire-proof materials, the most common existence plaster based, with added grout, and clay based. Prior to rubber moulds gelatine was used.

Casting jewellery and minor parts [edit]

The methods used for small parts and jewellery vary somewhat from those used for sculpture. A wax model is obtained either from injection into a rubber mould or by being custom-fabricated by carving. The wax or waxes are sprued and fused onto a rubber base, called a "sprue base". Then a metallic flask, which resembles a short length of steel pipe that ranges roughly from 3.5 to 15 centimeters tall and wide, is put over the sprue base and the waxes. Almost sprue bases have a round rim which grips the standard-sized flask, holding information technology in place. Investment (refractory plaster) is mixed and poured into the flask, filling it. It hardens, then is burned out as outlined above. Casting is normally washed straight from the kiln either by centrifugal casting or vacuum casting.

The lost-wax process tin can be used with whatever cloth that can burn, melt, or evaporate to get out a mould cavity. Some automobile manufacturers use a lost-foam technique to brand engine blocks. The model is made of polystyrene foam, which is placed into a casting flask, consisting of a cope and drag, which is then filled with casting sand. The foam supports the sand, allowing shapes that would exist impossible if the process had to rely on the sand solitary. The metal is poured in, vaporizing the cream with its heat.

In dentistry, gold crowns, inlays and onlays are made past the lost-wax technique. Application of Lost Wax technique for the fabrication of cast inlay was outset reported by Taggart. A typical gold alloy is almost 60% gold and 28% silver with copper and other metals making upwards the rest. Conscientious attending to tooth preparation, impression taking and laboratory technique are required to make this type of restoration a success. Dental laboratories make other items this manner as well.

Textile utilize [edit]

In this process, the wax and the material are both replaced past the metal during the casting process, whereby the fabric reinforcement allows for a thinner model, and thus reduces the amount of metal expended in the mould.[9] Show of this procedure is seen by the textile relief on the contrary side of objects and is sometimes referred to as "lost-wax, lost textile". This textile relief is visible on gold ornaments from burying mounds in southern Siberia of the ancient equus caballus riding tribes, such as the distinctive group of openwork gold plaques housed in the Hermitage Museum, St. petersburg.[9] The technique may have its origins in the Far East, equally indicated past the few Han examples, and the bronze buckle and gold plaques institute at the cemetery at Xigou.[10] Such a technique may also have been used to manufacture some Viking Age oval brooches, indicated by numerous examples with textile imprints such every bit those of Castletown (Scotland).[eleven]

Archaeological history [edit]

Center East [edit]

Some of the oldest known examples of the lost-wax technique are the objects discovered in the Nahal Mishmar hoard in southern Palestine (region), and which belong to the Chalcolithic menstruum (4500–3500 BC). Conservative Carbon-xiv estimates date the items to around 3700 BC, making them more than 5700 years one-time.[4] [5]

Most East [edit]

In Mesopotamia, from c. 3500–2750 BC, the lost-wax technique was used for modest-scale, and so subsequently big-scale copper and bronze statues.[four] One of the earliest surviving lost-wax castings is a small lion pendant from Uruk IV. Sumerian metalworkers were practicing lost-wax casting from approximately c. 3500–3200 BC.[12] Much later examples from northeastern Mesopotamia/Anatolia include the Great Tumulus at Gordion (late 8th century BC), every bit well every bit other types of Urartian cauldron attachments.[13]

South Asia [edit]

The oldest known example of the lost-wax technique comes from a 6,000-year-old (c. 4000 BC) copper, bicycle-shaped amulet found at Mehrgarh, Pakistan.[2]

Metallic casting by the Indus Valley Civilization began around 3500 BC in the Mohenjodaro area,[14] which produced 1 of the earliest known examples of lost-wax casting, an Indian bronze figurine named the "dancing daughter" that dates dorsum near 5,000 years to the Harappan period (c. 3300–1300 BC).[14] [fifteen] Other examples include the buffalo, bull and dog found at Mohenjodaro and Harappa,[6] [fifteen] [16] ii copper figures establish at the Harappan site Lothal in the district of Ahmedabad of Gujarat,[14] and likely a covered cart with wheels missing and a consummate cart with a commuter found at Chanhudaro.[6] [16]

During the postal service-Harappan menses, hoards of copper and statuary implements made past the lost-wax process are known from Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal.[14] Gold and copper ornaments, apparently Hellenistic in style, made by cire perdue were plant at the ruins at Sirkap. One case of this Indo-Greek art dates to the 1st century BC, the juvenile figure of Harpocrates excavated at Taxila.[14] Bronze icons were produced during the 3rd and 4th centuries, such equally the Buddha image at Amaravati, and the images of Rama and Kartikeya in the Guntur district of Andhra Pradesh.[14] A further 2 bronze images of Parsvanatha and a small hollow-cast bull came from Sahribahlol, Gandhara, and a standing Tirthankara (2nd, third century Advertizement) from Chausa in Bihar should be mentioned here likewise.[14] Other notable bronze figures and images have been found in Rupar, Mathura (in Uttar Pradesh) and Brahmapura, Maharashtra.[xiv]

Gupta and post-Gupta menstruation bronze figures accept been recovered from the following sites: Saranath, Mirpur-Khas (in Pakistan), Sirpur (District of Raipur), Balaighat (well-nigh Mahasthan now in Bangladesh), Akota (most Vadodara, Gujarat), Vasantagadh, Chhatarhi, Barmer and Chambi (in Rajesthan).[fourteen] The statuary casting technique and making of statuary images of traditional icons reached a loftier stage of development in South Republic of india during the medieval menstruation. Although statuary images were modelled and cast during the Pallava Period in the eighth and ninth centuries, some of the nearly beautiful and exquisite statues were produced during the Chola Period in Tamil Nadu from the tenth to the twelfth century. The technique and art of fashioning bronze images is still skillfully practised in S India, specially in Kumbakonam. The distinguished patron during the tenth century was the widowed Chola queen, Sembiyan Maha Devi. Chola bronzes are the almost soughtafter collectors' items past art lovers all over the world. The technique was used throughout India, every bit well as in the neighbouring countries Nepal, Tibet, Ceylon, Burma and Siam.[15]

Egypt [edit]

The Egyptians were practicing cire perdue from the mid 3rd millennium BC, shown by Early Dynastic bracelets and gold jewellery.[17] [18] Inserted spouts for ewers (copper water vessels) from the 4th Dynasty (Old Kingdom) were made by the lost-wax method.[18] [nineteen] Hollow castings, such every bit the Louvre statuette from the Fayum discover appeared during the Middle Kingdom, followed by solid cast statuettes (like the squatting, nursing mother, in Brooklyn) of the 2d Intermediate/Early on New Kingdom.[19] The hollow casting of statues is represented in the New Kingdom by the kneeling statue of Tuthmosis IV (British Museum, London) and the caput fragment of Ramesses V (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge).[20] Hollow castings become more detailed and go on into the Eighteenth Dynasty, shown past the blackness bronze kneeling figure of Tutankhamun (Museum of the University of Pennsylvania). Cire Perdue is used in mass-production during the Late Period to Graeco-Roman times when figures of deities were bandage for personal devotion and votive temple offerings.[12] Nude female person-shaped handles on statuary mirrors were bandage past the lost-wax process.[12]

Gilt ibex figurine from the Late Cycladic period (17th century BC). Nigh 10cm long with lost-wax cast feet and head and repoussé trunk, from an excavation on Santorini.

Greece, Rome, and the Mediterranean [edit]

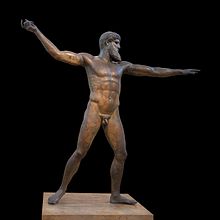

The lost-wax technique came to be known in the Mediterranean during the Statuary Age.[21] Information technology was a major metalworking technique utilized in the aboriginal Mediterranean world, notably during the Classical flow of Greece for large-scale bronze bronze[22] and in the Roman world.

Direct imitations and local derivations of Oriental, Syro-Palestinian and Cypriot figurines are establish in Late Statuary Age Sardinia, with a local production of figurines from the 11th to 10th century BC.[21] The cremation graves (mainly 8th-7th centuries BC, but continuing until the beginning of the fourth century) from the necropolis of Paularo (Italian Oriental Alps) contained fibulae, pendants and other copper-based objects that were made by the lost-wax process.[23] Etruscan examples, such as the bronze anthropomorphic handle from the Bocchi collection (National Archaeological Museum of Adria), dating back to the 6th to 5th centuries BC, were made by cire perdue.[24] Well-nigh of the handles in the Bocchi collection, equally well as some bronze vessels found in Adria (Rovigo, Italy) were made using the lost-wax technique.[24] The better known lost-wax produced items from the classical world include the "Praying Male child" c. 300 BC (in the Berlin Museum), the statue of Hera from Vulci (Etruria), which, like about statues, was cast in several parts which were so joined together.[25] Geometric bronzes such as the 4 copper horses of San Marco (Venice, probably 2nd century) are other prime number examples of statues bandage in many parts.

Examples of works made using the lost-wax casting process in Aboriginal Greece largely are unavailable due to the common practice in later periods of melting downwardly pieces to reuse their materials.[27] Much of the bear witness for these products come from shipwrecks.[28] As underwater archaeology became feasible, artifacts lost to the sea became more accessible.[28] Statues similar the Artemision Bronze Zeus or Poseidon (institute virtually Cape Artemision), as well as the Victorious Youth (found about Fano), are ii such examples of Greek lost-wax bronze bronze that were discovered underwater.[28] [29]

Some Belatedly Bronze Age sites in Cyprus have produced cast statuary figures of humans and animals. One case is the male person figure found at Enkomi.[30] 3 objects from Cyprus (held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York) were cast by the lost-wax technique from the 13th and 12th centuries BC, namely, the amphorae rim, the rod tripod, and the bandage tripod.[xxx]

Other, earlier examples that show this assembly of lost-wax cast pieces include the bronze caput of the Chatsworth Apollo and the statuary caput of Aphrodite from Satala (Turkey) from the British Museum.[31]

Bronze ritual altar with extensive patterns. From the Country of Chu in central Cathay, before 552 BC

East asia [edit]

Revised: There is neat variability in the utilise of the lost-wax method in East Asia. The casting method to make bronzes till the early phase of Eastern Zhou (770-256 BCE) was almost invariably section-mold procedure.[32] Starting from effectually 600 BCE, there was an unmistakable ascent of lost-wax casting in the Central Plains of Cathay, start witnessed in the Chu cultural sphere.[33] Further investigations take revealed this non to exist the case as it is clear that the slice-mould casting method was the main technique used to industry bronze vessels in China.[34] The lost-wax technique did non appear in northern China until the 6th century BC.[35] Lost-wax casting is known as rōgata in Japanese, and dates back to the Yayoi period, c. 200 BC.[15] The most famous slice made by cire perdue is the bronze image of Buddha in the temple of the Todaiji monastery at Nara.[15] It was made in sections between 743 and 749, allegedly using seven tons of wax.[15]

Southeast Asia [edit]

The inhabitants of Ban Na Di were casting bronze from c. 1200 BC to 200 AD, using the lost-wax technique to industry bangles.[36] Bangles fabricated by the lost-wax process are feature of northeast Thailand.[35] Some of the bangles from Ban Na Di revealed a dark grey substance between the central dirt core and the metal, which on assay was identified every bit an unrefined form of insect wax.[35] [36] It is probable that decorative items, like bracelets and rings, were made past cire perdue at Non Nok Tha and Ban Chiang.[half-dozen] There are technological and textile parallels between northeast Thailand and Vietnam concerning the lost-wax technique.[half dozen] The sites exhibiting artifacts made by the lost-mould process in Vietnam, such as the Dong Son drums, come from the Dong Son, and Phung Nguyen cultures,[6] such as one sickle and the figure of a seated individual from Get Mun (near Phung Nguyen, the Bac Bo Region), dating to the Go Mun phase (stop of the Full general B catamenia, up until the 7th century BC).[36]

The Gloucester Candlestick, early 12th century, 5&A Museum no. 7649-1861

Northern Europe [edit]

The Dunaverney (1050–910 BC) and Little Thetford (1000–701 BC) flesh-hooks have been shown to be made using a lost-wax process. The Piffling Thetford flesh-claw, in particular, employed distinctly inventive structure methods.[37] [38] The intricate Gloucester Candlestick (1104–1113 AD) was made equally a single-slice wax model, then given a complex system of gates and vents before being invested in a mould.[eight]

Detailed 9th century bronze of a coiled snake, bandage by the lost wax method. Igbo-Ukwu, Nigeria

Sculpture from the Ife state using a lost-wax casting technique, Nigeria, late 11th-14th century.

West Africa [edit]

Bandage bronzes are known to have been produced in Africa past the 9th century AD in Igboland (Igbo-Ukwu) in Nigeria, the 12th century AD in Yorubaland (Ife) and the 15th century AD in the kingdom of Benin. Some portrait heads remain.[15] Benin mastered statuary during the 16th century, produced portraiture and reliefs in the metal using the lost wax procedure.[39]

Americas [edit]

The lost-wax casting tradition was developed by the peoples of Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, northwest Venezuela, Andean America, and the western portion of Southward America.[xl] Lost-wax casting produced some of the region's typical aureate wire and delicate wire decoration, such as fine ear ornaments. The process was employed in prehispanic times in Colombia's Muisca and Sinú cultural areas.[41] Ii lost-wax moulds, one consummate and one partially broken, were found in a shaft and chamber tomb in the vereda of Pueblo Tapado in the municipio of Montenegro (Department of Quindío), dated roughly to the pre-Columbian menstruum.[42] The lost-wax method did not appear in Mexico until the 10th century,[43] and was thereafter used in western Mexico to make a wide range of bell forms.[44]

Literary history [edit]

Indirect evidence [edit]

The Berlin Foundry Cup, early on 5th century BC

Some early literary works allude to lost-wax casting. Columella, a Roman writer of the 1st century Ad, mentions the processing of wax from beehives in De Re Rustica, maybe for casting, as does Pliny the Elderberry,[45] who details a sophisticated procedure for making Punic wax.[46] 1 Greek inscription refers to the payment of craftsmen for their piece of work on the Erechtheum in Athens (408/7–407/6 BC). Clay-modellers may use clay moulds to make terra cotta negatives for casting or to produce wax positives.[46] Pliny portrays[45] Zenodorus every bit a well-reputed ancient artist producing bronze statues,[47] and describes[45] Lysistratos of Sikyon, who takes plaster casts from living faces to create wax casts using the indirect process.[47]

Many bronze statues or parts of statues in antiquity were cast using the lost wax process. Theodorus of Samos is ordinarily associated with bronze casting.[45] [48] Pliny also mentions the utilize of pb, which is known to help molten statuary flow into all areas and parts of complex moulds.[49] Quintilian documents the casting of statues in parts, whose moulds may have been produced past the lost wax procedure. Scenes on the early-5th century BC Berlin Foundry Cup depict the cosmos of bronze statuary working, probably by the indirect method of lost-wax casting.[50]

Direct evidence [edit]

India [edit]

The lost-wax method is well documented in aboriginal Indian literary sources. The Shilpa Shastras, a text from the Gupta Period (c. 320-550 AD), contains detailed information about casting images in metal. The 5th-century AD Vishnusamhita, an appendix to the Vishnu Purana, refers directly to the modeling of wax for making metal objects in chapter XIV: "if an image is to be fabricated of metallic, it must showtime be made of wax."[14] Chapter 68 of the ancient Sanskrit text Mānasāra Silpa details casting idols in wax and is entitled Maduchchhista Vidhānam, or the "lost wax method".[14] [15] The 12th century text Mānasollāsa, allegedly written by Male monarch Someshvara III of the Western Chalukya Empire, also provides detail near lost-wax and other casting processes.[14] [15]

In a 16th-century treatise, the Uttarabhaga of the Śilparatna written by Srïkumāra, verses 32 to 52 of Chapter ii ("Linga Lakshanam"), give detailed instructions on making a hollow casting.[xiv] [15]

Theophilus [edit]

An early medieval author Theophilus Presbyter, believed to exist the Benedictine monk and metalworker Roger of Helmarshausen, wrote a treatise in the early-to-mid-twelfth century[51] that includes original work and copied information from other sources, such as the Mappae clavicula and Eraclius, De dolorous et artibus Romanorum.[51] It provides step-by-step procedures for making various articles, some by lost-wax casting: "The Copper Wind Chest and Its Conductor" (Chapter 84); "Tin Cruets" (Chapter 88), and "Casting Bells" (Affiliate 85), which call for using "tallow" instead of wax; and "The Cast Censer". In Chapters 86 and 87 Theophilus details how to separate the wax into differing ratios before moulding and casting to achieve accurately tuned small musical bells. The 16th-century Florentine sculptor Benvenuto Cellini may have used Theophilus' writings when he cast his bronze Perseus with the Caput of Medusa.[fifteen] [52]

America [edit]

A brief 1596 Advertizing account past the Spanish writer Releigh refers to Aztec casting.[xv]

Gallery [edit]

-

This statuary piece entitled Lazy Lady, by the sculptor Rowan Gillespie was cast using the lost-wax process.

-

A wax model is sprued with vents for casting metal and for the release of air, and covered in heat-resistant material.

-

A bandage in bronze, still with spruing

-

A bronze cast, with part of the spruing cut away

-

A nearly finished statuary casting. Only the core supports have yet to be removed and closed

-

Illustration of stepwise bronze casting past the lost-wax method

-

The Blätterbrunnen of 1976 by Emil Cimiotti, as seen 2022 in the urban center middle of Hanover, Federal republic of germany. A lost-wax method was used for the bronze leaves.

Notes [edit]

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. [1] [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ a b Thoury, M.; et al. (2016). "High spatial dynamics-photoluminescence imaging reveals the metallurgy of the earliest lost-wax cast object". Nature Communications. vii: 13356. Bibcode:2016NatCo...713356T. doi:10.1038/ncomms13356. PMC5116070. PMID 27843139.

- ^ Jairazbhoy, Rafique Ali, The Spread of Ancient Civilisations (Great United kingdom, New Horizon, 1982) p. 9

- ^ a b c Moorey, P.R.S. "Early Metallurgy in Mesopotamia". In Maddin 1988

- ^ a b Muhly, J.D. "The Ancestry of Metallurgy in the One-time World". In Maddin 1988

- ^ a b c d e f Agrawal, D. P. (2000). Ancient Metal Technology and Archeology of South Asia. A Pan-Asian Perspective. New Delhi: Aryan Books International. ISBN978-81-7305-177-7.

- ^ McCreight, Tim (1991). The Complete Metalsmith: An Illustrated Handbook. Davis Publications. ISBN978-0-87192-240-3.

- ^ a b Maryon, Herbert (1954). Metalwork and Enamelling, a Practical Treatise on Aureate and Silversmiths' Work and Their Allied Crafts (3rd ed.). Chapman & Hall.

- ^ a b Bunker, E.C. Lost Wax and Lost Textile: An Unusual Aboriginal Technique for Casting Gilded Belt Plaques. In Maddin 1988

- ^ Zhungeer Banner, western inner Mongolia, 3rd-1st centuries BC

- ^ Smith, K.H. (2005). "Breaking the Mould: A Re-evaluation of Viking Historic period Mould-making Techniques for Oval Brooches". In Bork, R.O. (ed.). De Re Metallica: The Uses of Metallic in the Middle Ages. AVISTA studies in the history of medieval technology, science and fine art. Vol. 4. Ashgate. ISBN978-0-7546-5048-5.

- ^ a b c Scheel, B. (1989). Egyptian Metalworking and Tools. Shire Publications. ISBN978-0-7478-0001-9.

- ^ Azarpay, G. (1968). Urartian Art and Artifacts. A Chronological Report . Berkeley and Los Angeles: Academy of California Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j 1000 fifty g Kuppuram, Govindarajan (1989). Ancient Indian Mining, Metallurgy, and Metal Industries. Sundeep Prakashan. ISBN978-81-85067-28-v.

- ^ a b c d east f grand h i j thou l Krishnan, M.V. (1976). Cire perdue casting in India. Kanak Publications.

- ^ a b Kenoyer, J. M. & H. Yard.-Fifty. Miller, (1999). Metal Technologies of the Indus Valley Tradition in Islamic republic of pakistan and Western Republic of india., in The Archaeometallurgy of the Asian Old World., ed. V. C. Pigott. Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Museum.

- ^ Ogden, J., 1982. Jewellery of the Ancient Earth, London: Trefoil Books.

- ^ a b Darling, A. Southward., (1990). Non-Ferrous Materials, in An Encyclopaedia of the History of Engineering, ed. I. McNeil London and New York: Routledge.

- ^ a b Ogden, J. (2000). Metals, in Aboriginal Egyptian Materials and Technology, eds. P. T. Nicholson & I. Shaw Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Aldred, Yard. Egyptian Art in the Days of the Pharaohs 3100 - 320 BC. London: Thames and Hudson.

- ^ a b LoSchiavo, F. "Early Metallurgy in Sardinia". In Maddin 1988

- ^ Fullerton, Mark D. (2016). Greek Sculpture. The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. p. 139. ISBN978-ane-119-11531-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Giumlia-Mair, A.; Vitre, Southward.; Corazza, S. "Iron Historic period Copper-Based Finds from the Necropolis of Paularo in the Italian Oriental Alps". In Archaeometallurgy in Europe 2003

- ^ a b Bonomi, S.; Martini, 1000.; Poli, Grand.; Prandstraller, D. (September 2003). Modernity of Early Metallurgy: Studies on an Etruscan Anthropomorphic Bronze Handle. Archaeometallurgy in Europe. Milan: Associazione Italiana di Metallurgia.

- ^ Neuburger, A., 1930. The Technical Arts and Sciences of the Ancients, London: Methuen & Co. Ltd.

- ^ Mattusch, Ballad C. (1997). The Victorious Youth. Los Angeles, California: Christopher Hudson. p. 10. ISBN0-89236-470-10.

- ^ Fullerton, Mark D. (2016). Greek Sculpture. The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. pp. 139–40. ISBN978-i-119-11531-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b c Sparkes, Brian A. (1987). "Greek Bronzes". Hellenic republic & Rome. 34 (2): 152–168 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Lloyd, James (2012). "The Artemision Statuary". Earth History Encyclopedia . Retrieved December 7, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Schorsch, D.; Hendrix, E. "The Production of Relief Ornament on Cypriot Statuary Castings of The Late Bronze Age". In Archaeometallurgy in Europe 2003

- ^ Maryon, Herbert (1956). "Fine Metallic-Work". In Vocaliser, E. J. H. Charles; Hall, A. R.; Williams, Trevor I. (eds.). The Mediterranean Civilizations and The Middle Ages c. 700 BC. to c. Advertizement. 1500. A History of Applied science. Vol. II. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN978-0-19-858106-2. OCLC 491563676. ; Encounter too Dafas, K. A., 2019. Greek Large-Calibration Bronze Statuary: The Late Primitive and Classical Periods, Institute of Classical Studies, School of Advanced Study, Academy of London, Message of the Institute of Classical Studies, Monograph, BICS Supplement 138 (London).

- ^ Peng, Peng (2020). Metalworking in Bronze Historic period Red china: The Lost-Wax Process By Peng Peng. Cambria Press. pp. 19–22.

- ^ Peng, Peng (2020). Metalworking in Bronze Historic period People's republic of china: The Lost-Wax Process By Peng Peng. Cambria Press. p. 99.

- ^ Meyers, P. "Characteristics of Casting Revealed past the Study of Ancient Chinese Bronzes". In Maddin 1988

- ^ a b c White, J.C. "Early Due east Asian Metallurgy: The Southern Tradition". In Maddin 1988

- ^ a b c Higham, C. "Prehistoric Metallurgy in Southeast Asia: Some New Information from the Excavation of Ban Na Di". In Maddin 1988

- ^ Bowman, Sheridan; Stuart Needham. "The Dunaverney and Footling Thetford Mankind-Hooks: history, applied science and their position within the Later Bronze Age Atlantic Zone feasting circuitous". The Antiquaries Periodical. The Society of Antiquaries of London. 87. Archived from the original on 24 August 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Bowman, S (1953). "Tardily Bronze Age mankind hook, Little Thetford". Cambridgeshire HER. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Davidson, Basil (1971). African Kingdoms. New York: Time-Life Books, pp. 146(7).

- ^ Lechtman, H. "Traditions and Styles in Central Andean Metalworking". In Maddin 1988

- ^ Scott, D.A. (1991). "Technical Test of Some Golden Wire from Pre-Hispanic S America". Studies in Conservation. 36 (2): 65–75. doi:10.1179/sic.1991.36.2.65.

- ^ Bruhns, M. O. (1972). "Man". Two Prehispanic Cire Perdue Casting Moulds from Colombia.

- ^ Hodges, H., 1970. Technology in the Ancient Globe, London: Allen Lane The Penguin Press.

- ^ Hosler, D. "The Metallurgy of Ancient Westward Mexico". In Maddin 1988

- ^ a b c d Pliny. Natural History (AD 77).

- ^ a b Humphrey, J.Due west.; Oleson, J.P.; Sherwood, A.N., eds. (2003). Greek and Roman Technology: A Sourcebook: Annotated Translations of Greek and Latin Texts and Documents. Routledge. ISBN978-i-134-92620-6.

- ^ a b Jex-Blake, K. & E. Sellers, 1967. The Elderberry Pliny'south Chapters on The History of Fine art., Chicago: Ares Publishers, Inc.

- ^ Pausania, Description of Greece 8.14.8

- ^ Hurcombe, L.1000. (2014). Archaeological Artefacts as Material Culture. Routledge. p. 207. ISBN978-i-136-80200-iii.

- ^ Mattusch, C.C. (October 1980). "The Berlin Foundry Cup: The Casting of Greek Bronze Statuary in the Early 5th Century B.C.". American Journal of Archaeology. 84 (4): 435–444. doi:x.2307/504071. JSTOR 504071.

- ^ a b Theophilus (Presbyter.) (1963). Hawthorne, John 1000.; Smith, Cyril Stanley (eds.). On Divers Arts: The Foremost Medieval Treatise on Painting, Glassmaking, and Metalwork. Dover. ISBN978-0-486-23784-eight.

- ^ Thousand. D. (February 1944). "Cire Perdue". The Scientific Monthly. 58 (2): 158. Bibcode:1944SciMo..58..158D. JSTOR 18097.

References [edit]

- Forbes, R. J. (1971). Metallurgy in Antiquity, Office 1. Early Metallurgy, the Smith and His Tools, Gilt, Silver and Atomic number 82, Zinc and Statuary. Studies in Aboriginal Technology. Vol. eight. Brill. ISBN978-ninety-04-02652-0.

- Hart, Thou. H. & G. Keeley, 1945. Metal Work For Craftsmen, London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons.

- Hodges, H. (1995) [1864]. Artifacts. Bloomsbury Bookish. ISBN978-0-7156-2316-9.

- Jones, D. M. (ed.) (2001). Archaeometallurgy, London: English Heritage Publications.

- Konkova, Fifty.Five.; Korol, G.G. "South Siberian Imports in Eastern Europe in the tenth — the 13th centuries: Traditions of Metalworking". In Archaeometallurgy in Europe 2003

- Long, S. (October 1964). "Cire Perdue Copper Casting in Pre-Columbian Mexico: An Experimental Approach". American Antiquity. 30 (2): 189–192. doi:x.2307/278850. JSTOR 278850.

- McArthur, Thou., 2005. The Arts of Asia. Materials, Techniques, Styles., London: Thames & Hudson.

- Noble, J.V. (October 1975). "The Wax of the Lost Wax Process". American Journal of Archæology. 79 (four): 368–9. doi:x.2307/503070. JSTOR 503070.

- Peng, Peng (2020). Metalworking in Bronze Age China: The Lost-Wax Process . Cambria Press. ISBN9781604979626.

- Taylor, South. Eastward., (1978). Dark-Age Meal Casting; An Experimental Investigation into the Possibility of using Wax Models for the Formation of Clay-Slice Moulds, with special reference to the Industry of Pairs of Bandage Objects., in The Section of Archaeology Cardiff: Academy of Cardiff, 97.

- Trench, Lucy (2000). Materials & Techniques in the Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Lexicon . University of Chicago Press. ISBN978-0-226-81200-7.

- Maddin, Robert, ed. (1988). The beginning of the use of metals and alloys: papers from the 2d International Conference on the Beginning of the Use of Metals and Alloys, Zhengzhou, China, 21–26 October 1986. MIT Press. ISBN978-0-262-13232-ix. OCLC 644557973.

- Archaeometallurgy in Europe: International Conference : 24-25-26 September 2003, Milan, Italia : Proceedings. Associazione Italiana di Metallurgia. 2003. ISBN978-88-85298-50-7.

External links [edit]

| External video | |

|---|---|

| | |

| |

- Andre Stead Sculpture - The Statuary Casting Process Archived 2016-11-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Metal Art of Bastar Photos

- "Flash blitheness of lost-wax casting procedure". James Peniston Sculpture. Retrieved 2007-x-24 .

- National Museum of Wildlife Art's Virtual Foundry Archived 2008-05-sixteen at the Wayback Machine

- "Casting a Medal". Sculpture. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 2009-01-29. Retrieved 2007-09-22 .

- Reconstructing the Bronze Age Trundholm Sun Chariot

- 10/fifteen/1904;The " Cire-perdue " Process of Bronze Casting

- "André Harvey Lost Wax Process (Cire Perdue)". André Harvey (sculptor). Archived from the original on 2014-05-28. Retrieved 2014-06-18 .

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lost-wax_casting

0 Response to "Ap Art History Lost Wax Technique Lost Wax Technique"

Post a Comment